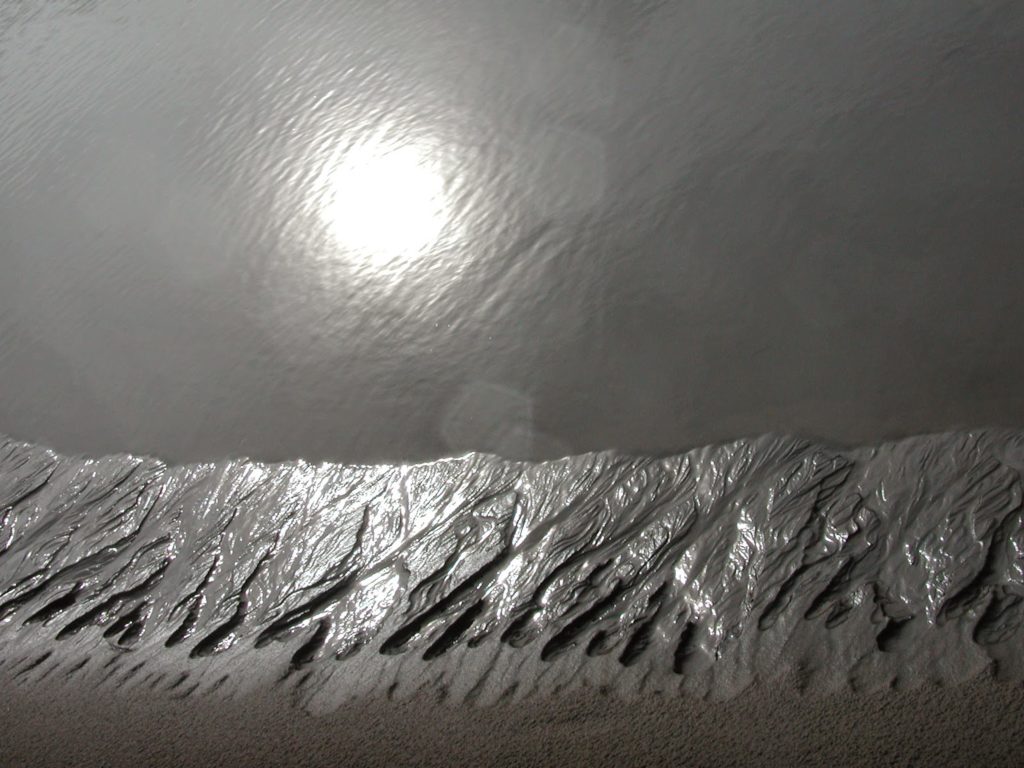

“Few phenomena gave me more delight than to observe the

forms which thawing sand and clay assume in flowing down the sides of a

deep cut on the railroad through which I passed on my way to the

village, a phenomenon not very common on so large a scale, though the

number of freshly exposed banks of the right material must have been

greatly multiplied since railroads were invented. The material was sand

of every degree of fineness and of various rich colors, commonly mixed

with a little clay. When the frost comes out in the spring, and even in a

thawing day in the winter, the sand begins to flow down the slopes like

lava, sometimes bursting out through the snow and overflowing it where

no sand was to be seen before. Innumerable little streams overlap and

interlace one with another, exhibiting a sort of hybrid product, which

obeys half way the law of currents, and half way that of vegetation. As

it flows it takes the forms of sappy leaves or vines, making heaps of

pulpy sprays a foot or more in depth, and resembling, as you look down

on them, the laciniated, lobed, and imbricated thalluses of some

lichens; or you are reminded of coral, of leopard’s paws or birds’ feet,

of brains or lungs or bowels, and excrements of all kinds. It is a

truly grotesque vegetation, whose forms and color we see

imitated in bronze, a sort of architectural foliage more ancient and

typical than acanthus, chiccory, ivy, vine, or any vegetable leaves;

destined perhaps, under some circumstances, to become a puzzle to future

geologists. The whole cut impressed me as if it were a cave with its

stalactites laid open to the light. The various shades of the sand are

singularly rich and agreeable, embracing the different iron colors,

brown, gray, yellowish, and reddish. When the flowing mass reaches the

drain at the foot of the bank it spreads out flatter into strands,

the separate streams losing their semicylindrical form and gradually

becoming more flat and broad, running together as they are more moist,

till they form an almost flat sand, still variously and

beautifully shaded, but in which you call trace the original forms of

vegetation; till at length, in the water itself, they are converted into

banks, like those formed off the mouths of rivers, and the forms of vegetation are lost in the ripple- marks on the bottom.

The whole bank, which is from twenty to forty feet high, is sometimes

overlaid with a mass of this kind of foliage, or sandy rupture, for a

quarter of a mile on one or both sides, the produce of one spring day.

What makes this sand foliage remarkable is its springing into existence

thus suddenly. When I see on the one side the inert bank- for the sun

acts on one side first- and on the other this luxuriant foliage, the

creation of an hour, I am affected as if in a peculiar sense I stood in

the laboratory of the Artist who made the world and me- had come to

where he was still at work, sporting on this bank, and with excess of

energy strewing his fresh designs about. I feel as if I were nearer to

the vitals of the globe, for this sandy overflow is something such a

foliaceous mass as the vitals of the animal body. You find thus in the

very sands an anticipation of the vegetable leaf. No wonder that the

earth expresses itself outwardly in leaves, it so labors with the idea

inwardly. The atoms have already learned this law, and are pregnant by

it. The overhanging leaf sees here its prototype. Internally, whether in the globe or animal body, it is a moist thick lobe, a word especially applicable to the liver and lungs and the leaves of fat (γείβω, labor, lapsus, to flow or slip downward, a lapsing; λοβός, globus, lobe, globe; also lap, flap, and many other words); externally a dry thin leaf, even as the f and v are a pressed and dried b. The radicals of lobe are lb, the soft mass of the b (single lobed, or B, double lobed), with the liquid l behind it pressing it forward. In globe, glb, the guttural g

adds to the meaning the capacity of the throat. The feathers and wings

of birds are still drier and thinner leaves. Thus, also, you pass from

the lumpish grub in the earth to the airy and fluttering butterfly. The

very globe continually transcends and translates itself, and becomes

winged in its orbit. Even ice begins with delicate crystal leaves, as if

it had flowed into moulds which the fronds of waterplants have

impressed on the watery mirror. The whole tree itself is but one leaf,

and rivers are still vaster leaves whose pulp is intervening earth, and

towns and cities are the ova of insects in their axils.”

Leave a Reply