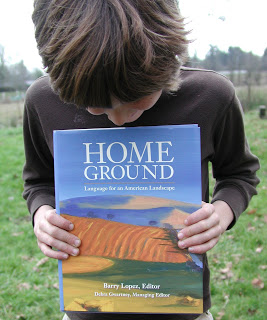

There are a few books out there that I think everyone living in this country should own or at least read in their lifetime. Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape, edited by Barry Lopez is one of these. Every term for the American landscape that you could think of, both common and obscure are included in this collection of over 850 definitions of landscape vocabulary written by 45 different writers, journalists, and novelists. Among these are Barbara Kingsolver (her home ground is the terminus of Walker Ridge, Holston River watershed, Virginia), Charles Frazier (the Southern Appalachians), Terry Tempest Williams (the Colorado Plateau), John Krakauer (Boulder County, Colorado), Pattiann Rogers (A mile east of Wildcat point, the site of Kit Carson’s last campfire, Colorado), and one of my favorite writers, Barry Lopez (McKenzie River, Oregon).

For those of you interested in things like sense of place, and connection to the landscapes we inhabit, this book is essential. It gives meaning to vocabulary we use describing places to which we may have never given any thought. Each definition is a mini essay, including place-specific examples of the landscape features, as well as some literary references and a little history. It’s nothing short of fascinating.

In the introduction, Barry Lopez writes, “Some of us in the United States can trace our family lines back many generations to, say, the Green Mountains of Western Vermont, the urban hills of the San Francisco peninsula, or the sandhills of western Nebraska; to small towns along the Mississippi River or a red-earth farm in Alabama. Many of us have come from ranching, farming, or logging families, and might have listened with a measure of envy while grandparents spoke of these places of origin, using a language so suited to the place being described it fit against it like another kind of air. A language capable of conveying the most evanescent of the place’s characteristics.

Today, the majority of us raise our families, go to school, find employment and locate much of our inspiration in urban areas. The land beyond our towns, for many, has become a generalized landscape of hills and valleys, of beaches, rivers and monotonous deserts. Almost against our wills the countryside of our parents’ and grandparents’ generations – the Salinas Valley we might once have pictured reading John Steinbeck, images of Sarah Orne Jewett’s Maine or the barefoot country of Eudora Welty’s stories, of Willa Cather’s Nebraska and New Mexico – almost without our knowing it, the particulars of these landscapes have slipped away from us. Asked, we might still conjure them, but we probably could no longer still name the elements that made them vivid in our memories.

It has become a commonplace observation about American culture that we are a people groping for a renewed sense of place and community, that we want to be more meaningfully committed, less isolated. Many of us have come to wonder whether modern American life, with its accelerated daily demands and its polarizing choices, isn’t indirectly undermining something foundational, something essential to our lives. We joke that one shopping mall looks just like another, that a housing development on the outskirts of Denver feels no different to us than a housing development outside Kansas City, but we are not always amused by such observations…

It is with these thoughts, about the importance of belonging, of knowing the comfort that a feeling of intimate association with place can bring, that we began work on Home Ground. We wanted to recall and explore a language more widespread today than most of us imagine, because we believed an acquaintance with it, using it to say more clearly and precisely what we mean, would bring us a certain kind of relief. It would draw us closer to the landscape upon which we originally and hopefully founded our democratic arrangement for governing ourselves, our systems of social organization, and our enterprise in economics. If we could speak more accurately, move evocatively, more familiarly about the physical places we occupy, perhaps we could speak more penetratingly, more insightfully, more compassionately about the flaws in these various systems which, we regularly assert, we wish to address and make better.”

One of the things I really love about this book is the breadth and variety of kinds of landscape vocabulary. There are, of coure, definitions of common landscape words like prairie, plain, hill, glacier, plateau, ravine, and desert. Then there are geological terms like scoria, protalus rampart, talus, strata and travertine. There are features named after parts of the human body (pointing strongly to the connection between people and place) like finger lake, eye, groin, toe-slope, tooth and shoulder. There are names with ecological associations like strip mine, clear cut, derelict land, tailings pond, and dust bowl. There are names borrowed from other lands and languages like dalles (French), esker (Irish Gaelic), krummholz (German), playa (Spanish), and local indigenous languages like pocosin (Algonquin), kipuka (Hawai’ian), and bogue (Louisiana Choctaw.) There are also those interesting names where you would never know what they are without this book, like cowbelly (a place where fine sediment settles in the slack water of slow creeks), gunk hole (a small, out of the way harbor), yazoo (a tributary that parallels the main stream for a long distance), and thank-you-ma’am (a bump or depression in a dirt road at an intersection.) Among my favorites are back forty, misfit stream, rainshadow, hill country, briar patch, and chickenhead.

Here are a few of the definitions I enjoyed:

A “Flat” is defined by D.J. Waldie as this: The transformation of North America from wilderness to marketable real estate needed flat land to farm and build towns on, and to make crossing the continent possible. One way to advertise land that could become farmland, a town site, or a roadbed was to name it Flat or Flats. Some flats point out the local vegetation: Cedar Flat, Oregon; Hickory Flat, Missouri; Yucca Flats, the Nevada nuclear test site; and Piney Flats, Tennessee. Some flats just locate the site: Yukon Flat in Alaska, Rail Road Flat in California, and Flatgap in Kentucky. Other flats are a problem: there are more than fifteen potentially unpleasant locations in the West named Alkali Flat or Flats. Then there’s Dead Ox Flat in the aptly named Malheur County, Oregon. The term is evocative, however it’s used. Flat is one of the words with which writers quickly sketch the West, as in this scene from Zane Grey’s novel The Light of Western Stars: “Far below lay the cedar flat and the foothills. Far to the west the sky was still clear, with shafts of sunlight shooting down from behind the encroaching clouds.”

A definition of “Cauldron” is given by Terry Tempest Williams as; A particularly chaotic type of gaping river hole, a cauldron is characterized by “big, squirrely, boiling water,” in the words of one river runner. River cauldrons form where rocks, which have accumulated on the riverbed at a spot where the river suddenly drops, scour out a bowl-shaped depression. The surface of the river churns and explodes here like a soup boiling over in a pot. Sulphur Cauldron, on the upper Yellowstone River in northwestern Wyoming, is one of many famed river cauldrons. Cauldrons are also a seacoast feature. When ocean swells and breakers surge into constricted openings in the seaward face of the land, they sometimes produce ferocious hydraulics – violent whirlpools, geysers, and suddenly collapsing haystacks of white water.

“Headwaters” is defined by Mary Swander: Most people visualize a headwater as a powerful gushy of water over a falls or a single bubbling brook high high in the mountains as the source of a stream. But in fact, rivers have no single source. A network of springs, creeks, streams, and tributaries drain into the upper portions of a river’s system to form its headwaters. These network waterways are often found in the mountains but may also include desert springs and seeps, wet meadows, or even bayou-like channels. The headwaters of a reservoir are the waters at the far upstream end, where the river empties into the lake. Headwater streams are critically important to the whole river system, providing habitat to the flora and fauna of their own ecosystems and delivering nutrients and organic material to downstream regions. Headwaters can also carry pollution and damage downstream. For example, the Mississippi River begins in Minnesota, carrying agricultural runoff pesticides and farm chemicals all the way to its mouth in New Orleans. The chemicals flush into the Gulf of Mexico, where they create a lifeless region of oxygen-depleted (hypoxic) water called the Dead Zone. In Moby-Dick, Hermal Melville wrote metaphorically of headwaters: “Our grand master is still to be named; for like royal kings of old times, we find the headwaters of our fraternity in nothing short of the great gods themselves.”

Barbara Kingsolver gives her definition of “Lick”; Salt licks are places, often along rivers and streams, where naturally occurring salt deposits attract animals that come to lick the earth for its mineral gifts. These areas tend to be rich in both biotic and human history. A good example is the Licking River, earlier known as the Great Salt Lick Creek, a 320-mile-long river arising in eastern Kentucky and flowing north into the Ohio. The salt licks along its banks drew down mastodons and other great mammals of the Pleistocene whose skeletons are today embedded in the substrate; they so greatly influenced the migratory routes of eastern bison that early European explorers counted more than one thousand at a time at the licks, and Daniel Boone told of seeing buffalo, “more frequently than I have ever seen cattle in the settlements.” Later, these same springs along the Licking became centers for the human industry of salt-making, strategically important Civil War sites,and, during the nineteenth century, home to bottling plants and grand hotels touting the health benefits of the waters from their springs. The craving of mammalian species for mineral salts is strong and timeless.

And, of course, I will include the definition for “Mountain” by Bill McKibben: A mountain is land that rises above the surrounding plain. But it is not simply higher than a hill; the very word mountain also implies a brand of majesty. On a mountain, normal processes are magnified – their steep slopes, for instance, mean streams flow faster and carry more rock of larger size, accelerating erosion. Mountains can create their own weather, as clouds dump their cargo on the windward side. And they carry their own heightened psychological charge as well; Thoreau, in a spiritual fright as he bushwhacked up Maine’s Katahdin, imagined that “some part of the beholder, even some vital part, seems to escape through the loose grating of his ribs as he ascends.” Through by conventional measurement the planet’s tallest mountains are all in Asia, Hawai’i can claim its most massive: by the reckoning of one geologist, measuring from the seafloor, the Mauna Loa volcano is the “largest projected landmass between Mars and the Sun.”

To really get to know a place, it helps to know the names it is called by. Reading books like this one, looking at a topographical map, or even talking to a local old-timer will provide you with a wealth of information concerning place. While looking into it, you may run across familiar terms from your childhood and you may run across some you never understood the meaning behind. From a simple name, you might learn a little about the history of the very piece of ground you stand upon, and what it meant to people who have stood there before you. I encourage everyone to make a point of getting to know their home ground as intimately as possible. Learn about it, read about it, and get out there and explore it. By becoming more familiar with the place you go about your life, there is a rich sense of rooted-ness to be gained. For it is a good feeling to truly feel at home.

Leave a Reply